Anti-phoenixing scheme bolstered.

In the 2018-19 Budget, the Government announced it will modernise the Australian Business Register and the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) registers onto a single platform that will be administered by the Australian Business Registrar within the Australian Taxation Office (ATO).

As part of those changes Schedule 2 of the Treasury Laws Amendment (Registries Modernisation and Other Measures) Bill 2018 amends the Corporations Act 2001 and the Corporations (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander) Act 2006 (CATSI Act) to introduce a director identification number (DIN) requirement.

Under the new law, directors must apply to the registrar for a DIN within 28 days, unless the registrar provides an exemption or extension. Once satisfied that the director’s identity is verified, the registrar must provide the director with a DIN. Transitional provisions say that current directors will have 15 months to apply for a DIN from when it becomes law.

Initially, the DIN requirements apply to only appointed directors and acting alternate directors—not, at least initially, extended to de facto or shadow directors. This reflects the broader registry regime operation applies to registered bodies, which does not generally extend to de facto and shadow directors.

One of the major pushes for the DIN is to assist regulators and external administrators to investigate director involvement in what may be repeated unlawful acts including illegal phoenix activity, which is estimated to cost the Australian economy between $2.9 billion and $5.1 billion annually.

Phoenixing occurs when company controllers deliberately avoid paying liabilities by shutting down an indebted company and transferring its assets to another company. This impacts on creditors who are unpaid for goods and services, employees through lost wages and/or superannuation entitlements, and the public through lost Government revenue.

Tracking directors involved in past phoenixing activity may also allow the ATO to request bonds when those directors seek to operate future businesses (i.e. request a new ABN) to provide some certainty for the payment of future taxation obligations.

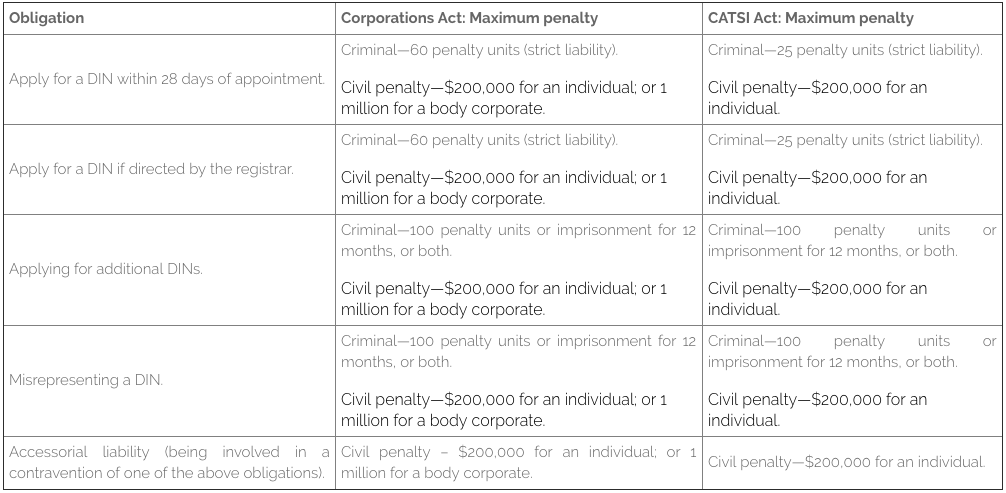

Significant civil and criminal penalties apply to DIN contraventions. The registrar may also issue infringement notices in relation to some contraventions. The maximum penalties applicable to each obligation in the Bill are detailed in the following table.

Breaching either of the first two obligations is a ‘strict liability’ offence that negates the condition to prove fault (for the regulator or prosecutor, as the case may be). The Government states that imposing strict liability to these obligations is necessary to ensure the integrity of the new DIN requirement that relates to corporate regulation.

Civil penalties also apply to those involved in contravening any of the obligations above, which is defined in sections 79 of the Corporations Act and 694-55 of the CATSI Act. They provide that a person is so involved if, and only if, the person has aided, abetted, counselled, procured, induced or been knowingly concerned or a party to the contravention, or has conspired with others to effect the contravention. The maximum civil penalty applicable under the Corporations Act is $200,000 for an individual or $1 million for a body corporate.

We think the measures are fair and should serve a positive motivation to really understand and appreciate what it means to be a director. We will be interested to see what effect this law will have on reducing the very real problem of phoenixing.