What rights does a bank with a GSI have over unsecured creditors?

The impact of a general security interest (GSI, also known as a security interest over all present and after-acquired property—AllPAAP), on the distribution of asset and other recovery proceeds in a liquidation can be confusing for stakeholders. Banks commonly hold a GSI over a company but a GSI can be held by anyone if the company enters into a valid and ‘perfected’ general security agreement.

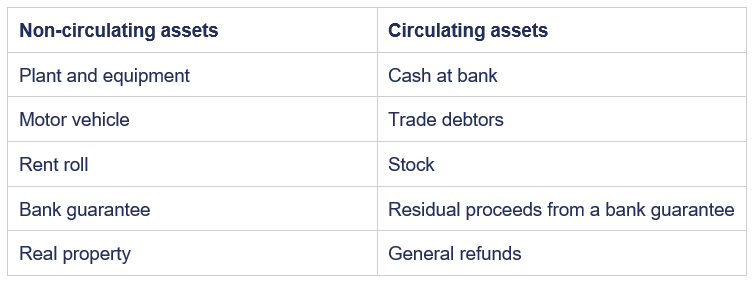

First, we must establish that all assets subject to a GSI will fall into two categories:

2. circulating assets.

These categories were previously known as “fixed and floating assets” (charges) before the Personal Property Securities Act 2009 (PPSA) commenced.

A GSI provides a security over all, or substantially all, of a company’s assets and the right to appoint a receiver. How asset sale proceeds are distributed will vary depending on the category of the asset sold, while other recoveries in a liquidation (e.g. insolvent trading and voidable transactions), will by-pass any priorities that a GSI affords.

Where a secured creditor does not appoint a receiver over the company, the liquidator effectively acts as a receiver to distribute asset recoveries in accordance with the security agreement and section 556 of the Corporations Act 2001. However, when a receiver is appointed, the priority distributions over circulating assets differ under section 433 of the Corporations Act.

Broadly speaking, a company’s non-circulating assets cannot be disposed of without the secured creditor’s consent, while circulating assets can be used, disposed, and be dealt with in the ordinary course of business without the need to obtain the secured creditor’s consent.

When categorising these assets, however, the security agreement must be considered along with the PPSA. Common asset classifications are as follows.

To give an example, a building contract may retain a bank guarantee during the defect liability period. A defect may arise during this time; however, the cost may not be known until after it is rectified. The bank guarantee could then be called upon and the residual proceeds released—12 months after the liquidation commences. To prevent the bank guarantee from being called on, the bank could pay the rectification costs separately to retain its rights as a non-circulating asset.

Let’s now examine the impact on how recoveries are distributed.

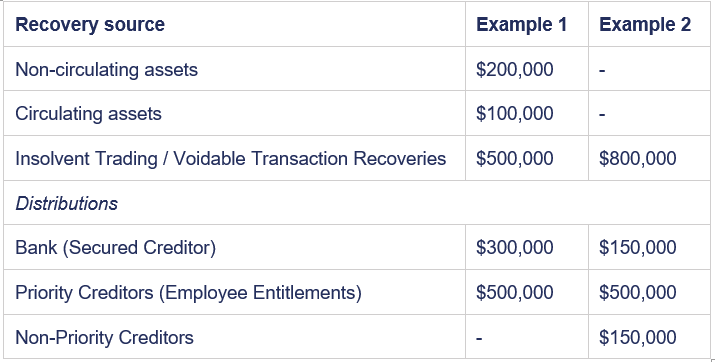

Relying on the categories above, the examples below (which do not consider a liquidator’s costs) focus on distributing funds to a bank with a GSI, priority creditors (employee entitlements) and ordinary (non-priority) unsecured creditors (e.g. trade creditors).

For the examples below, let’s say each creditor category—secured creditors, priority creditors, and non-priority creditors—is owed $500,000 and the source of recoveries are as follows.

Example 1

In this scenario, the bank (secured creditor) received $200,000 from non-circulating asset recoveries.

The priority creditors then received $100,000 from the circulating assets and the first $400,000 of the insolvent trading / voidable transaction recoveries.

The residual $100,000 from the insolvent trading / voidable transaction recoveries were then distributed to the bank as a right to subrogation (substitution) was enlivened for the priority creditor claims totalling $100,000 (Re Damilock Pty Ltd (In Liquidation) [2012] FCA 1445).

For the bank to be entitled to the right of subrogation however, it must provide its consent to the payment of employee entitlements, otherwise a breach of trust claim may be made against the liquidators.

Prior to the Damilock case and the case Cook v Italiano Family Fruit Company Case Pty Ltd (in Liquidation) (2010) 276 ALR 349, in which the Damilock case relied on, the position regarding a generally secured creditor’s rights to non-asset recoveries was not clear. I suspect however, the courts will be tested on specific scenarios in future.

Example 2

In this scenario, the bank received $0 from non-circulating asset recoveries.

The priority creditors also received $0 from the circulating assets but received the first $500,000 of the insolvent trading / voidable transaction recoveries.

The residual $300,000 from the insolvent trading / voidable transaction recoveries was then distributed equally between the bank and non-priority creditors.

Conclusion

Evidently, the source of recoveries will impact the distributions required to be made to a bank holding a GSI and unsecured creditors. This information may be important for directors to understand in relation to personal guarantees provided.