How the ATO is reacting to the hand it's been dealt.

In July 2021, I wrote an article: “ATO’s generosity won’t last forever”, which was published in Accountants Daily. The key points of the article were:

The Australian Taxation Office (ATO)’s collection activity had effectively ceased. The use of ATO driven bankruptcies and liquidations had drastically reduced.

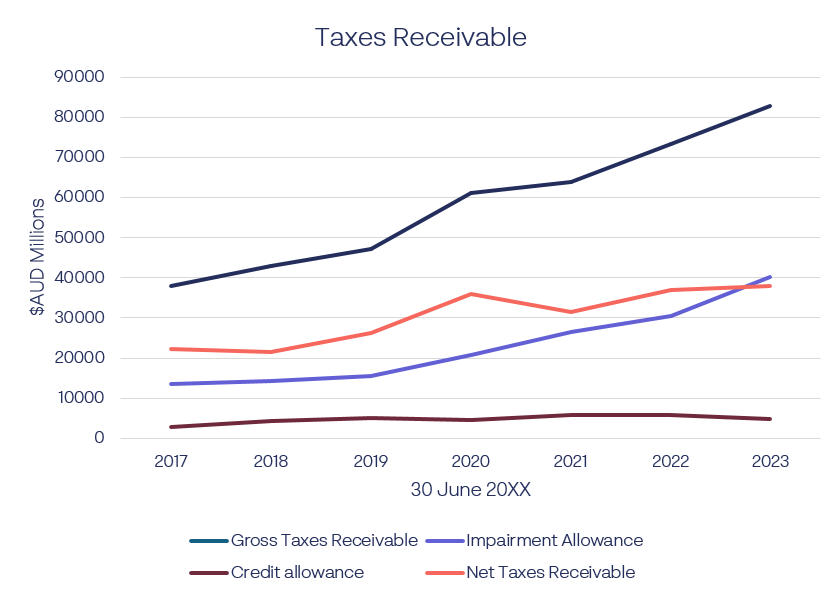

Between 2015 and 2020 the Federal Government’s accounts receivable had increased by 75%, from $20 billion to $36 billion.

Three years later, gross taxes receivable increased to $82.9 billion. However, the amount of impairment allowance (or “bad debts” allowance) in the Federal Government’s accounts has escalated from $13.6 billion in 2017 to $40.3 billion in 2023. That’s a 300% increase over six years.

Data via Commonwealth Consolidated Financial Statements.

Data via Commonwealth Consolidated Financial Statements.

Readers will observe that, in what may be a historical first, the impairment allowance exceeds net taxes receivable as at 30 June 2023.

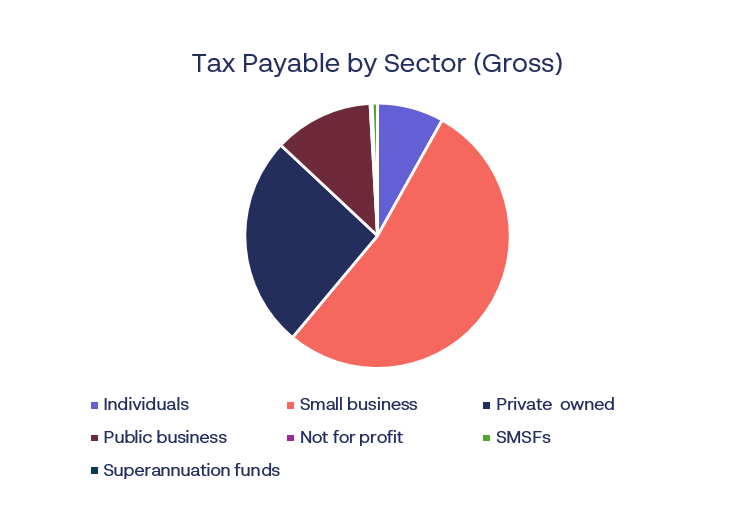

Who owes all of these taxes?

Small business is the biggest source of both collectible and uncollectable taxes. The breakup of taxpayer categories is depicted in the following chart:

Data via CA ANZ Tax Update June 2024.

Data via CA ANZ Tax Update June 2024.

The Federal Government’s balance sheet discloses that approximately half of the taxes receivable are not recoverable, the majority of it being owed by small businesses. An issue with the impairment allowance is that the ATO cannot write off core tax debt for small businesses. It can voluntarily allow for remission of general interest charge (GIC) (which it is increasingly reluctant to do), but that’s the limit of the Commissioner’s discretion.

The only way to compromise core tax debt is through a formal insolvency process. Prior to 1 January 2021, insolvency processes were often either thought to be expensive, or were considered to come with several downsides for small businesses.

Composition of debt

Approximately 57% of debt is what the ATO terms “High Priority Debt”. These are liabilities that stem from superannuation guarantee, pay as you go (PAYG) and goods and services tax (GS T). The ATO will be escalating collection on these debts very quickly. From the ATO’s perspective, businesses are holding these amounts on behalf of the employee or the Commonwealth. If we simplify their logic, when an invoice is paid, 1/11th of that receipt is the ATO’s. When wages are paid, the business is holding the PAYG and superannuation components on behalf of the employee. The ATO does not consider these amounts to be the Company’s money and their tolerance for businesses not remitting these amounts is decreasing.

Collection strategies to intensify

To be clear, the ATO’s collection strategies have already intensified during the 2024 financial year. The ATO has already been ramping up issuing Director Penalty Notices, garnishee notices and reporting tax liabilities to credit report agencies.

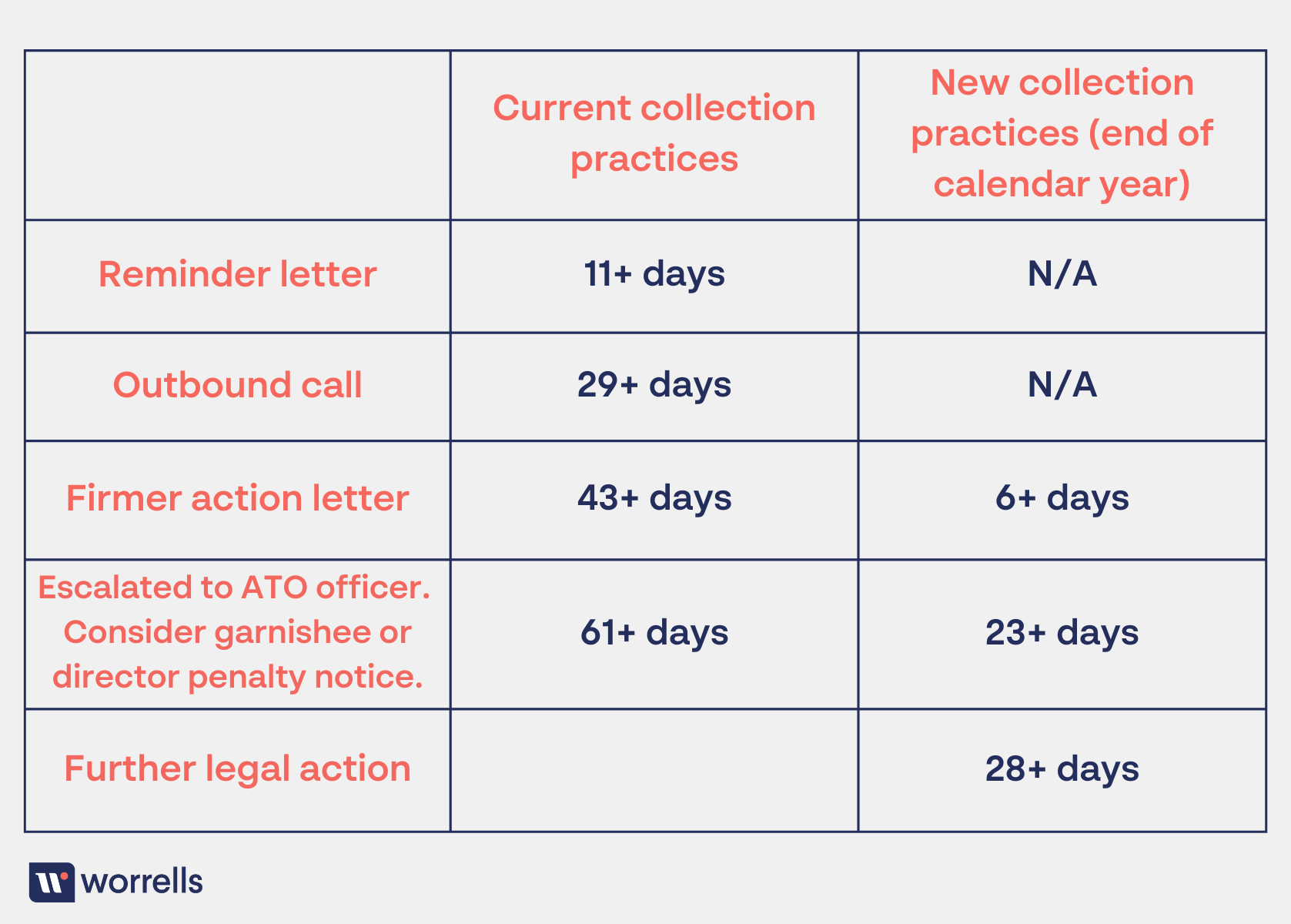

The ATO is further tightening its collection processes, with a focus on High Priority Debt. The collection process for taxpayers who do not engage with the ATO will be a lot tighter and less forgiving. I compare the current and proposed collection timeframes below:

As readers can see, the window where the ATO uses a much softer approach to encourage payment will be removed, with the ATO going straight to a firmer action letter. After that firmer action letter, they are intending implement enforcement actions as quickly as 23 days.

What are director penalty notices?

This is a topic in and of itself, but in a short a director penalty notice (DPN) allows the ATO to pierce the corporate veil and make a director personally liable for some company taxation liabilities. To read further about director penalty notices, click here to view our other articles on the subject.

Rise of the small business restructure (SBR)

Prior to the introduction of the small business restructuring regime, if a small business had a large tax debt, the ATO was obliged to collect it all. Businesses can only enter into a payment plan for the total balance of their tax debt. As there was no commercial option to compromise part of core tax liabilities, I argue that the previous regime encouraged the use of phoenix activity as it could become virtually impossible for a business to pay back its tax obligations. Additionally, the costs of a voluntary administration to restructure (and reduce) core tax debt was sometimes considered prohibitive to many small businesses.

To use the Government’s own words:

“Before these reforms [the small business restructure regime] came into effect, Australia’s corporate insolvency system was based on a one size-fits-all model that imposed the same duties and obligations, regardless of the size and complexity of the administration. High costs and rigid processes created barriers to access and depleted the limited resources held by distressed small businesses. In doing so, the system failed to account for the needs of small businesses. The impact of these issues risked becoming more acute because of the economic consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic, and a potential increase in numbers of businesses facing financial distress.”

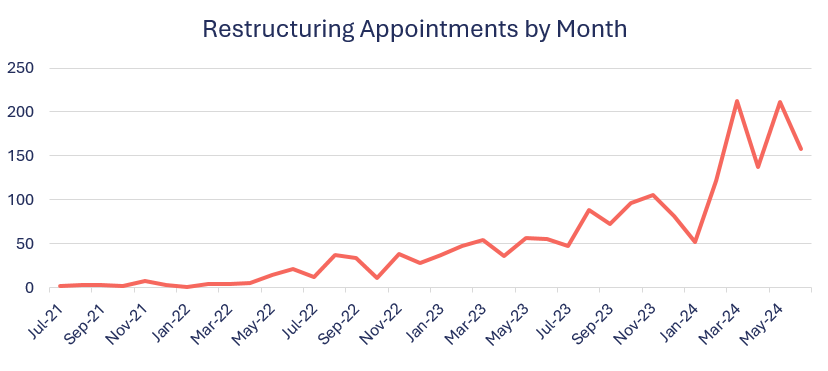

The use of SBRs took a while to gain traction, but exploded in 2023:

One of the key reasons that SBRs have been so successful is that the ATO have engaged positively with the process.

SBRs have been a positive force in the corporate landscape. It is rare that insolvencies can result in all stakeholders winning. In my opinion they have been a win-win:

The ATO is able to compromise on core tax debt. This allows for the reduction of uncollectible debt that was otherwise on the books.

The restructuring practitioner has examined the business regarding solvency, providing a filter that means that “zombie ” companies are not restructured (companies that only earn enough to operate and service debt, but not pay off debt or generate a profit).

It saves the cost of winding up small businesses, which often costs circa $5,000 in legal fees, which the ATO rarely recovers. This is taxpayer money that was previously going to law firms, which also resulted in cases clogging up the Courts’ dockets.

It saves jobs. Viable businesses are able to continue employing going forward.

It reduces phoenix activity, as the same corporate shell continues to be used and assets are not moved out of the shell.

The Director retains control of the business throughout the process, resulting in large cost savings.

The cost of restructuring is much less than the previously available restructuring mechanism (voluntary administration/deed of company arrangement) which was not always suitable for small businesses.

It leaves many licenses intact, which were previously impacted by voluntary administration.

If you think that SBRs are too good to be true, there’s a catch: a director/company can only use the process once every seven (7) years. This provides a safeguard to prevent abuse of the process.

The landscape going forward

With pressure set to ramp up in the form of reduced firmer action timeframes, businesses with large tax liabilities are walking on a razor’s edge. If a client does not have a payment plan in place with the ATO, there should be a fallback plan in place. If you think your client’s debt falls into the Federal Government’s $40b impairment allowance, it may be time to consider restructuring options. Reach out to your local Worrells office for a complimentary and obligation-free chat to learn more about restructuring options.